Photojournalists revel in the unexpected resonance of their work. Journalistic ethics prevent photographers from staging, rehearsing, or otherwise influencing their subjects to look or behave in a given way. Any artistic framing, lighting, or intention must come from the subject's movements, the photographer's timing, and relative positions of the subject and journalist as events unfold.

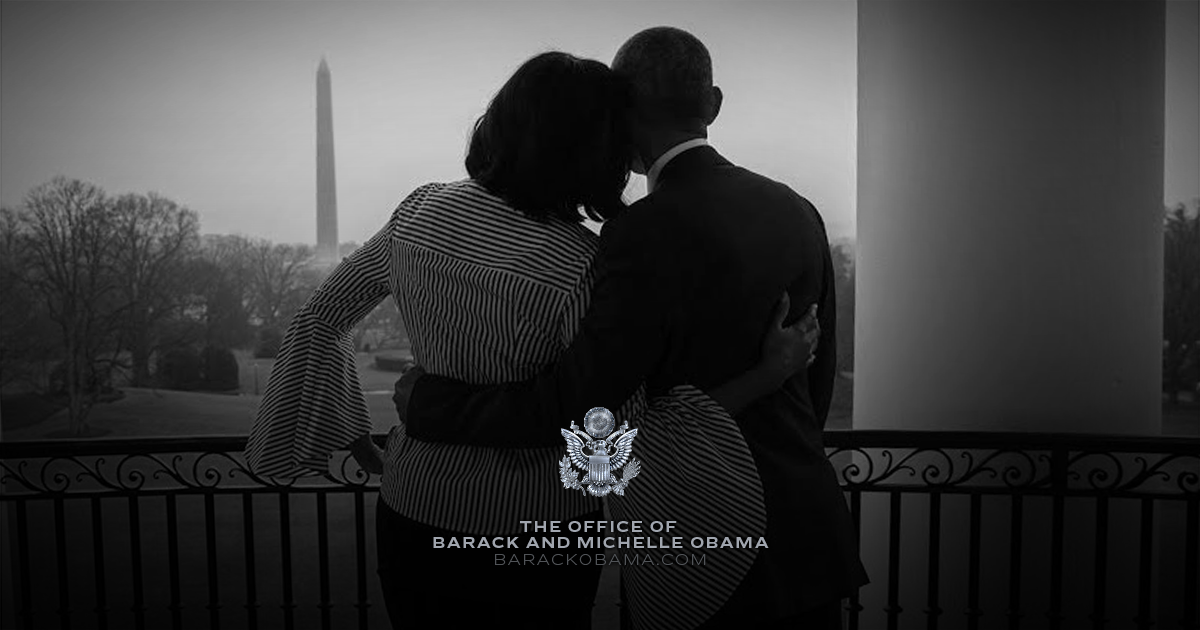

In the case of the American President, the press are given access within a restricted area, and are generally limited to documenting staged appearances. Even in the limited circumstances of presidential photojournalism, pool photographers have captured images of unexpected depth. For example, a number of formal and semantic properties in Jabin Botsford's presidential photograph for the

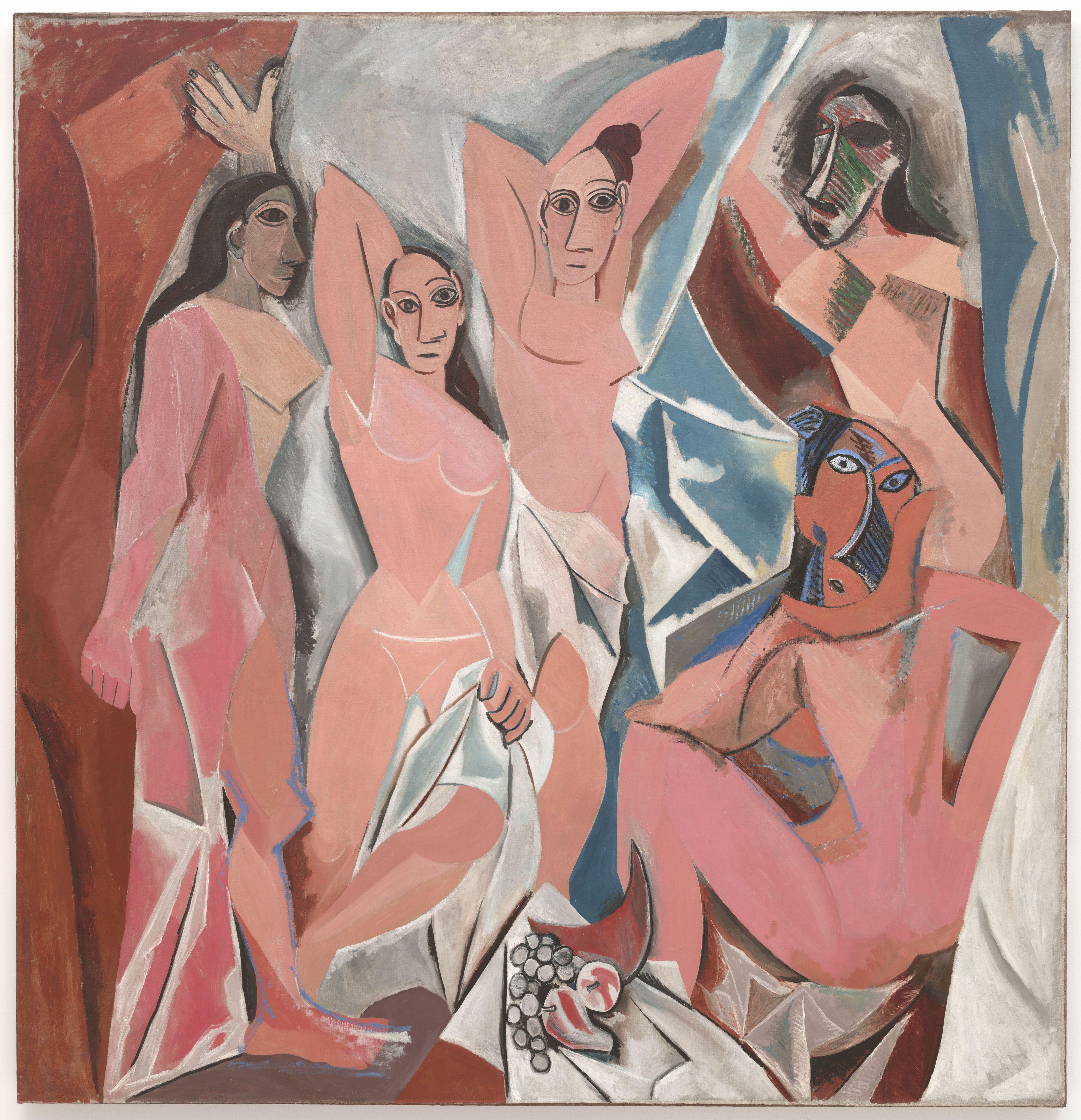

Washington Post dated March 15, 2018 resonate with Pablo Picasso's 1907 cubist masterpiece

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

On March 15, 2018, President Trump met with Leo Varadkar, the Prime Minister or Ireland, members of the American Petroleum Institute, and Bill Gates. Jabin Botsford's photograph was taken in the East Room, where President Trump presented Irish Prime Minister Varadkar with an early St. Patrick's Day gift. Botsford's tightly framed photograph does not reveal the President's green tie, nor the first lady's green dress, nor the presence of the Irish delegation. The image itself, by revealing no details that would situate the it in time or space, would not be published on the day it was taken, either. Rather, the

Washington Post would use this staff photographer's image to headline two articles on March 18, 2018, one about nondisclosure agreements and the other about "fake memos." That the date of the photograph did not match the date of the featured articles caught my attention, as did the photograph's notorious date, the Ides of March. Perhaps the photographer had hoped to capture a Roman bust or the profile of Caesar, but on that day, at that moment, the subject wore a more interesting countenance: the oblique gaze of a cubist painter's model.

The two images under consideration share what I call the "oblique gaze," in which the subject looks without directly seeing. The oblique gaze distinct from the more recognizable "side-eye," for while the side-eye communicates disapproval or contempt, the oblique gaze lacks such communicative connotations. Rather, the oblique gaze eschews both the confrontation of eye contact and the emotion of the sidelong look. Looking obliquely, the subject demonstrates awareness of being seen, yet neither meets nor reacts to the gaze of the beholder.

Picasso's leftmost demoiselle, known as the curtain-pulling figure, demonstrates awareness of being seen: her oblique gaze and rigid posture emphasize the arresting gaze of the beholder. Her visage is small, out of perspective with the rest of her body, and darkly painted, again in stark contrast with the rosy tone of her nude figure. Furthermore, the shadows and highlights on her face have been inverted from the lighting scheme of the scene. By formally disconnecting the curtain-pulling figure's face from her own body and from the lighting scheme of the tableau, Picasso asserts the mental detachment of the figure.

Contrast the oblique gaze of the curtain-pulling figure with the direct gaze of the two Iberian figures, the negative, black hole gaze of the masked figure, or the wild-eyed gaze of the crouching figure. The Iberians, the central nude figures posed with draperies, return the gaze of the beholder with the languid detachment of an artist's model. The masked figure poses assertively, yet her gaze is hidden in the negative space between mask and countenance. The cubist crouching figure turns to the beholder volte-face, one eye blue and the other white, with an unexplained form cupping her face, perhaps a hand. Here, as with the vestigial hand of a man in the top left corner-- the men were pictured in studies for Demoiselles but were excised from the final canvas-- Picasso has perhaps hinted at the masculine hand turning the face of the crouching figure to meet the masculine gaze of the beholder. Men, removed from view, are in control: revealing the women behind the curtain, posing them with draperies, masking, turning, unmasking their faces to suit the male gaze.

Like the curtain-pulling demoiselle, the President eyes the press corps obliquely, acknowledging not the male gaze of desire, but the blunt gaze of the free press. With wary detachment, he neither returns the media gaze, nor reacts emotionally to their presence. Just as the demoiselles are confined within the canvas of their brothel, the President is confined to the stage of his office. Ostensibly one of the most powerful men in the world, he cannot escape the omnipresent media glare.

By illustrating formal connections between these two figures, the photographer draws the gaze of the beholder to the deeper semantic resonance of a sitting American president affiliated with prostitutes, pornographic actresses, and playmates, who has been accused of rape and has confessed to sexual assault.

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies: Setting Sun, donated to Musée de l'Orangerie 1922. http://www.musee-orangerie.fr/en/article/set-orangerie

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies: Setting Sun, donated to Musée de l'Orangerie 1922. http://www.musee-orangerie.fr/en/article/set-orangerie